Edited by

B.A. SISSONS

Introduction

This is the story of the Victoria University tramping club's first fifty years. It is only one of many possible stories, but while I am very conscious that an abundance of facts and reminiscences have escaped us, our version I trust is at least not unrepresentative.

The first positive action towards a fiftieth anniversary celebration occurred in the middle of 1970. An informal committee was mustered and it made sporadic preparations throughout the rest of the year. Meanwhile, work began. on this publication when the editor visited various past members, gleaning information, and soliciting the articles which appear here under the title 'Five Decades'. Then, in order to give these articles a context, present members were asked to collect material from which they could write about certain other aspects of the club. In the absence of a formal history, for which we lacked both the time and the historian, these sections together with a selection of trip accounts, must suffice to tell our story.

We received technical and financial assistance from the Students' Association, which apart from temporarily financing the printing also made a grant of $50.

In the later stages many people lent a hand. John Thomson, in correspondence with the editor who had by then retreated to Christchurch, helped with the final editing and selection of material. The layout was designed by Simon Arnold, and Noel Sissons took over the increasingly complicated task of liaison. We are indebted to Pam McQueen for the pen drawing on the cover, and also to Margaret Keys who typed much of the copy.

Finally, I should like to thank those members, past and present whose enthusiasm for this jubilee publication has encouraged us all in its production.

B.A. Sissons

Ways and Means in the Home Country

B. A. Sissons

Tramping

Club outings began in the first term of 1921, when Spike records that day trips were run to Red Rocks, Kaukau, Days Bay and the Karori Hills. Outings to such places remain part of the club's activity, which now includes most areas of the Hutt watershed and along the local coastline within its day trip programme. Weekend trips, before the close of 1921, had looked into both the Orongorongos and Tararuas. With the ferry service to Eastbourne, the Orongos soon became the favourite stamping ground. Access across the watersheds of the Gollans and Wainui Valleys made this area ideal for weekend expeditions. The club purchased a share in Tawhai Hut, sited just off the Five Mile Track near Jacob's Ladder, and so gained both a base for longer trips and a comfortable rendezvous for easier weekends of pleasure and discussion.

Adventurous spirits were not to remain satisfied with the Orongorongos alone; the greater extent and height of the Tararuas presented an obvious challenge. The Southern Crossing was an established route by this time and received due attention from the VUCTC. Although the Tararua Survey had been completed in 1873, little of it had been preserved, other than the skeletal map drawn by L. Smith in 1881. Routes to the more remote areas, especially in the north, had to be rediscovered. Prof. Boyd-Wilson and Dr. J.S. Yeates were the first on Mt. Crawford after the surveyors. Crossing into the Otaki Valley from the head of the Waitatapia in January 1925, they re-opened that route.

While the T.T.C. were instrumental in much of this reopening process, many of the VUCTC trips in the early days of the 1920's and '30's were of an exploratory nature. Without the comprehensive map first published in 1936, or the accumulated experience of generations of trampers in the area, it was often a matter of finding the details out for one's self. There were still unexplored pockets in the Tararuas in the early thirties, in the upper basins of rivers such as the Hector and Waiohine.

In the thirties, with a flourishing club and more organisation, came truck transport. In a small club there was generally only one truck hired, and to be economical it had of necessity to be filled. Trucks brought the whole new field of the Northern Tararuas within the scope of weekend trips, but must have restricted planning in many other ways. The club became closely associated with its truck drivers, the Mangin brothers. They were almost honorary members of the club, giving much more than the mere minimal service. Arrangements for second rendezvous points, depending on weather and river conditions, were undertaken, and when parties were late, it was they who formed the first link in the chain of the rudimentary Search and Rescue organisation.

With fewer huts and longer access tracks, winter crossings were more arduous expeditions than now, although large parties did occasionally go through, as, for example, when Geoff Wilson took a party of twenty over the northern crossing in 1931. Due, apparently, to short cycle climatic changes, there was more snow in the earlier decades of this century. Zotov, in a report on Tararua vegetation published by the Royal Society in 1939, states that the tops were in general continuously covered with snow for five months in winter. Skiing in the Tararuas, at Holdsworth and Kime, although no doubt hard work, was common enough, and cutting steps at such places as the Beehives was far from unusual.

By the sixties truck transport was no longer used by 'varsity trampers. Organisation in general has waned, and leadership appears less important. Today smaller parties sometimes bordering on the private, are more common. Train or railcar followed by a taxi to the road-end, followed by a two to four hour walk, constitutes the usual Friday night start. Transport home on Sunday is often by thumb - hitching has become accepted, and, some would say, an art. The flexibility of this rail-taxi-thumb system has allowed for greater variety of weekend trips, and variety has in fact become the essence of the club's Tararua tramping. The Forest Service has placed huts at short intervals along the tops (could Prof. Boyd-Wilson have foreseen three huts on the ridge between him and West Peak when he stood on Crawford in 1925?), marked tracks down most leading spurs, bridged difficult river crossings, signposted the tops and opened up access ways. This, combined with better equipment, better maps, and sadly, less snow in winter, has made formerly difficult crossings more commonplace. With problems of access, routefinding and shelter rapidly disappearing, tramping has developed in several ways. People are attempting much longer weekend and day trips. The Schormann-Kaitoke trip is often completed in a weekend and one day middle and northern crossings have come into vogue. Although no official VUWTC party has completed a Schormann-Kaitoke, middle and northerns have been done. One party went from Vosseler hut via Hector, Neill, Neill Forks, High Ridge, Holdsworth and Girdlestone to sleep on Brockett in an unsuccessful attempt to climb all the 5000ft peaks in a weekend, retreating over Mitre in a nor'wester next day. What have become known as masochist trips are another aspect of modern VUW tramping in the Tararuas. These trips deliberately seek out untracked and unlikely to be tracked areas, often at the scrub level, for example, a direct crossing of Bannister Basin, of a traverse of Tawiri Kohukohu or the Camelbacks. The suffering of course is more exquisite in snow.

|

|

Among recent Tararua exponents Nick Whitten figures prominently with such epics as his Pipe Bridge, Waiopehu, Oriwa, Mid Otaki, Kelliher, Nicholls, Waiohine, Shingleslip Knob, Angle Knob Hut, Holdsworth Lodge in three days, with a variety of weather and a fairly large party to his credit. During Queen's Birthday Weekend 1966, Tom Clarkson organised a club effort to visit all known huts in the Tararuas. 41 people in 9 parties visited 47 huts, missing only 8. Carried out in only moderate weather, the scheme was considered a great success by the participants.

Rockclimbing

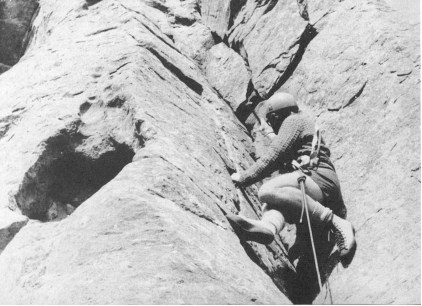

Keen rockclimbers and many lesser-motivated scramblers make frequent excursions during the year to Titahi Bay and Baring Head. 'The Bay' is more popular, and with its greater variety and height presents more interesting problems than does Baring Head, which nevertheless still provides good practice especially for basic instruction courses.

Since early exponents like C.J. Read showed novices the ropes, the Slab and the Pinnacle have been standard routes. Others such as the Three Sisters and the Baby's Bottom became recognised later. With the recent publication of a Guide Book to Titahi Bay, more climbs have been identified and a greater variety is now being attempted. Finding protection on the typical New Zealand greywacke these has always been a problem although the introduction of new equipment, notably Jam nuts, has helped keep the safety factor up with the standard of climbing.

As in most fields there has been a swing away from the organised trip, with more informal days spent by the sea. Indeed, the stated purpose of rock climbing is often seen to give ground to other pleasures like swimming, sunbathing, lazing and eating. But the trend towards specialisation is also evident, as in everything else.

A variation to rockclimbing which has developed recently is urban night climbing. Popular overseas and long known in Christchurch, it received little attention in Wellington until some of the activities of VUNK (Victoria University Night Climbers Club_) were reported in Heels '69. With innumerable possibilities from a Girdle Traverse of Parliament Buildings to a dirretissima on the Carillon, and added difficulties in possible brushes with the law, this shadowy sport has many attractions. It is a sport, however, which has yet to be, as you might say, officially recognised.

Further Afield

Christmas Trips

B.A. Sissons

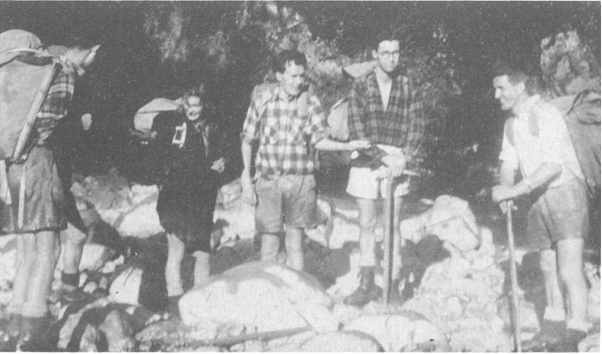

Christmas trips are almost as old as the club. The first set out for National Park in the summer of 1923-4, and they have been run every year since with the single exception of 1942. The pattern for trips remained fixed until the end of the forties. A sub-committee would be formed during the year to decide on the area to be visited, and to organise transport, gear and food. Planning was detailed and meticulous. Accounts were kept and schedules issued to all participants. After the forties there was a change to smaller and more informal trips, the tramping was more commonly to less frequented valleys, and the climbing, especially in recent years, considerably more ambitious. But of course, what is now well known was often virtually unexplored fifty years ago, and climbs are easier when others are known to have been up before you.

The first recorded Christmas trip was in 1923. It was in the nature of a holiday, at Tongariro National Park and Taupo. 'Ruapehu was climbed', Spike reported, 'and all the lesser mountains.' There was a lengthy stay at Tokaanu, and a visit to Wairakei'. More difficult tramping followed when S.A. Wiren led the next two trips into the Urewera. Both parties set out from Waikaremoana, the first coming out at Waiotapu and the second following down the flooded Whakatane River. It was little-known country then, but offered fine tramping, and unlike most back-country, had some notable historic associations, especially with Te Kooti and the Prophet Rua to recommend it. The first club trip to go south left for the Waimakariri in January 1926. Wiren was keen to sort out several cartographical problems which Carrington had not yet solved when he was drowned. With Carrington's own map he was able to propose several names for peaks and passes in the area, many of which have been adopted, but his only climb was up the still unnamed peak on the main divide near Mt. Armstrong. Then, after a visit to N.W. Nelson and ascents of Arthur and Paul, there were three further trips to National Park, by the end of which few areas within or around the park were unvisited, or peaks unclimbed. These early trips, although the parties often ran to twenty or so, were usually filled by invitation - a system analogous to the present one, but imposed, one guesses, because of the attractive ease rather than the difficulty of the expeditions.

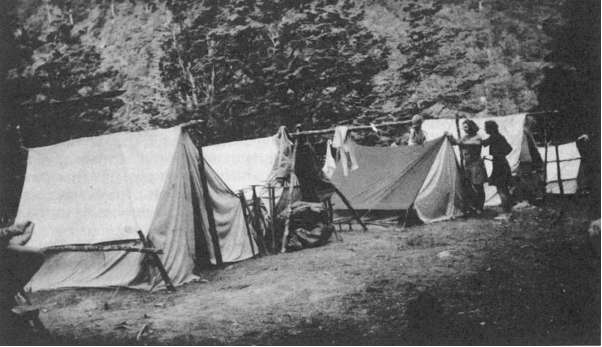

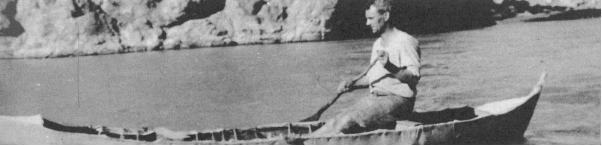

In the 1930's, however, trips were open to all who thought themselves sufficiently fit. This had an immediate effect upon the club: numbers soared and trips were often planned to include a base camp. The Spensers were first visited in 1930. From the head of Lake Rotoroa, Misery was climbed, and the E. Sabine explored to the lakes at the head. The party then retreated to the comforts of a cottage at St. Arnaud. This area, owing to its accessibility, its easy travelling and its pleasant beauty became the one most frequently seen by the club in the next three decades. The following year, two trips were run. The first, to the Dee branch of the Clarence, was made notable by Boyd-Wilson's building a canoe; the other party walked from the Franz Joseph Glacier over Haast Pass to Wanaka, with pack horses to carry gear and help in crossing the rivers. The Otira trip of 1932 managed, in spite of bad weather, to climb Baron and the low peak of Rolleston. At the same time, Boyd-Wilson led some tramping of an unusual kind. After what Spike describes as a strenuous few days at National Park, the party crossed Lake Taupo by launch and during the next few days followed the main trunk line north through the King Country to Pukemako. The second Spensers trip followed in 1933. From a base camp established on the Rainbow branch of the Wairau, a sub-party completed a round trip through the Travers and Sabine headwaters and then everyone went down the Clarence and out to Hanmer. F. Eggars led the other 1933 trip of thirty people, who for ten days boated, fished and tramped around Tuna Bay in Pelorous Sound.

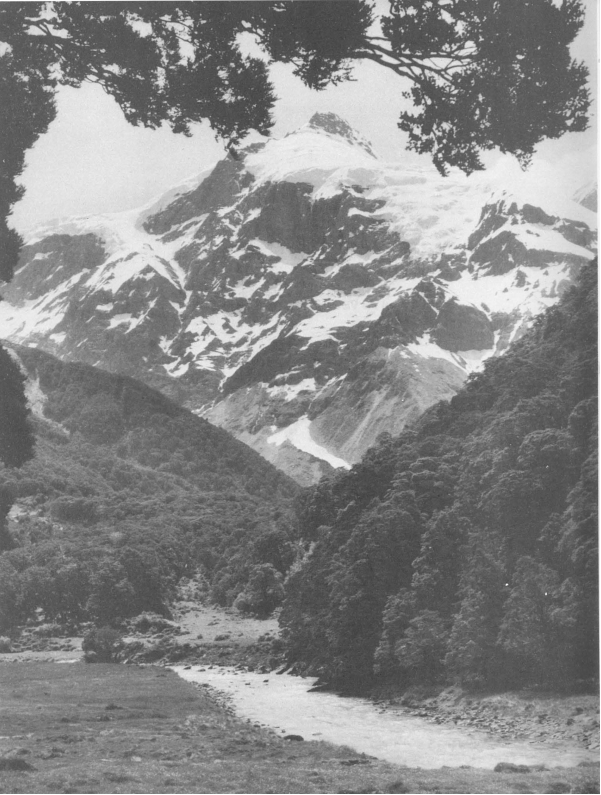

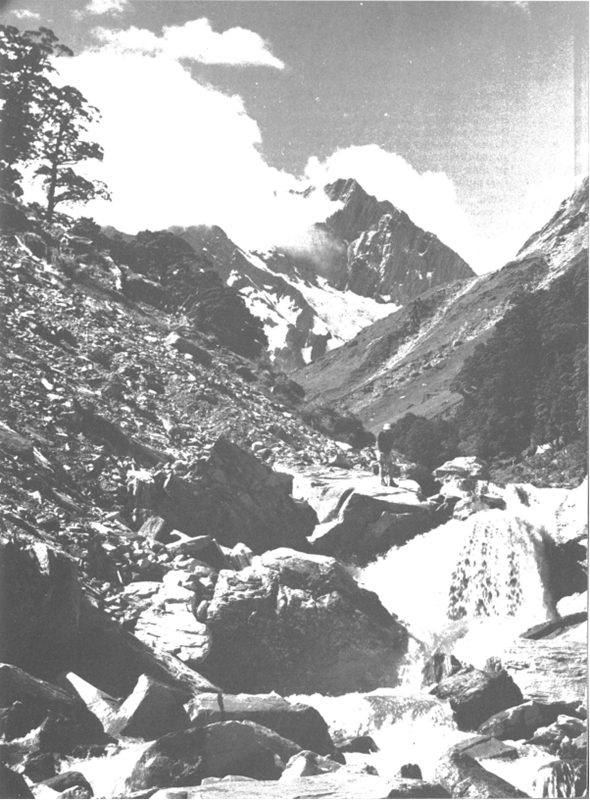

Venturing further south in 1934, D. Viggers led a party to the upper Hollyford. After seeing the views from Gertrude Saddle and Key Summit, the party crossed to the Routeburn and Lake Wakatipu. Next year he took people to the Waimakariri and the Wilberforce. Another 1935 party, having camped for several days in the Waipakihi River in the Kaimanawas, crossed the Desert Road to Waihohonu Hut, picking up food on the way and in the following days climbed Ngauruhoe and to the crater on Ruapehu. In 1936 from a base camp in the lower Travers valley climbs were completed on the Camel and Mt. Travers, and attempts were made on Little Twin and Mt. Hopeless. On these base camp trips large amounts of gear were taken - the tents in particular were heavy - and from this particular trip there is a photograph showing a game of teniquoits in progress, which is an indication of the mixed objectives of the large party. Base camp was in fact the base for a wide variety of holiday activities. A successful Arthur's Pass trip followed in 1937. Spike recorded fifteen peaks were climbed and the first known traverse of Falling Mt. from Tarn Col was achieved. Among the fifteen peaks were Rolleston and those of the Polar Range. From Lewis Pass the 1938 party traversed Cannibal Gorge and put a base camp in the Waiau River. Mts Lucretia, Technical and Travatone were climbed in various amounts of cloud and at the end of the trip the party sampled the pleasures of the hot spring at Maruia. Two trips to the Waimak followed, a Three Pass trip in 1939 and a base camp trip to the White confluence in 1940. On the latter trip, in addition to a traverse of the Shaler Range, a large party climbed Mt. A.P. Harper.

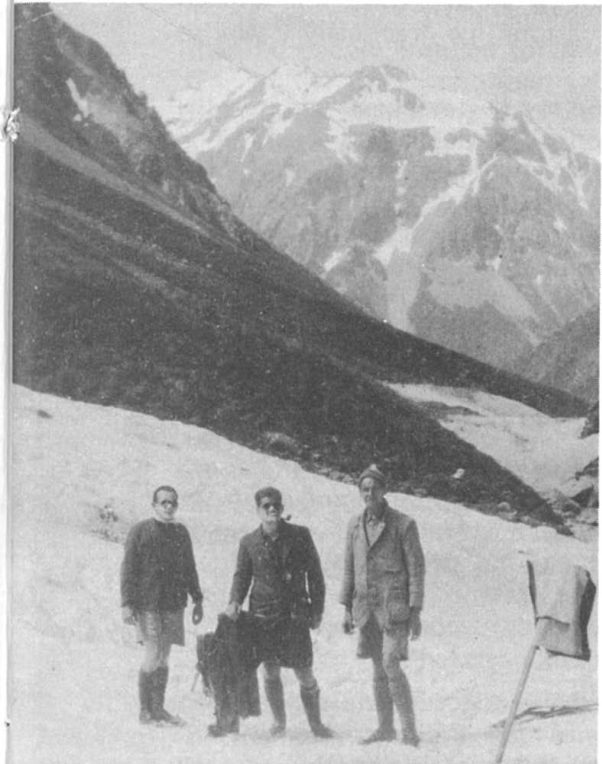

In 1934 when there was often little to distinguish TTC and VUCTC trips a mixed party made several climbs in the Godley. This interest in climbing, though it slackened a little through the thirties underwent a resurgence in the early forties, prompted especially by the enthusiasm of J.B. Butchers. In 1941 Butchers and R. Collin led another successful Godley trip. From Godley Hut the party proceeded to a camp up glacier with skis and biscuit tin sledges. Large parties climbed Mts Gordon and Wolsely. With decreased activity in the next few years due to the war there was no trip in 1942 but in 1943 M. Benge led a trip to the Cobb Valley in Nelson and A.O. McLeod led a Waimakariri trip in 1944. The next large trip followed in 1945 when Butchers led another climbing trip, this time to the Wilkin, when many climbs were made, some of them new.

There were two trips in 1946. John McCreary led a Waimak-Anticrow-White-Bealy trip, pictures of which show the party in deep snow at the head of the White. Bad weather prevented the projected Three Pass trip. The other trip went to the Hopkins valley and coincided with an NZAC meet there. Members of the party made climbs from the head of the valley, for example Prudence Peak, and also from the Huxley and Elcho sidestreams. On New Years Day 1947 the whole party set out to make a crossing of the Neumann Range. At 11.00am, just after lunch on the crest of the range, eleven of the party of nineteen were involved in a wet snow slide. S. Allaway and R. Dickson were killed and three others seriously injured. Soon after contact had been made with the Glen Lynn homestead 25 miles down the Dobson, a large rescue operation was mounted. This was safely completed when the injured were brought out on a truck which had been driven to the head of the valley. The trend to larger parties reached a climax in 1947 when Butchers led a party of 38 into the Spensers. The minds of present day members boggle at the organisational difficulties alone. Such a large party was bound to fragment, some preferred to stay around the camp while others climbed the surrounding hills. Eventually a through party left over Travers Saddle bound for Lewis Pass while the remainder returned to St. Arnaud. 1948 saw the club return to the Spensers. Ron Ellis led a some what smaller party up the Matakitaki River valley. Rain prevented a projected crossing to the Waiau but the party managed to repeat the previous year's climb of Faerie Queene and add ascents of Malling and Humboldt before returning down valley. Terry Qualter engineered an intricate double Dart-Rees trip in 1949. One party made a side trip up the Greenstone at the start to allow the second party time to get ahead and hopefully get some climbing in. Both parties eventually crossed Snowy Saddle and followed the Rees out to Glenorchy, having climbed Cleft and Cunningham.

Although private trips had been run since the thirties they were not very numerous. However, in the fifties private trips became more common, and by the late sixties they took so predominant a part that the official club Christmas Trip faded in significance. Only a few of these many trips can here be mentioned.

Christmas 1950-51 marks the first Olivine trip run by the club. The route was from the Routeburn to the Olivine, the Pyke, to Big Bay and the Hollyford. Since then Olivine trips have been run in 1952, '56, '59, '62, '66, and '70, so that the region has been frequented by the club almost as much as the more accessible and easier areas of Arthur's Pass and the Spensers. Most of the valleys surrounding the Olivine Ice Plateau have been visited and only the Northern Olivine Range remains relatively unexplored by the club. The Spensers have retained their popularity with at least eight Christmas visits over the same period, the St. Arnaud-Lewis Pass through trip being the most popular. In recent years this area has also come in for more attention during the shorter holidays.

In 1956 and 1957 two Godley trips were run. Both parties made climbs in the Godley before crossing Classen and Tasman Saddles to the Tasman Glacier and the Hermitage. In 1962 Bill Stephenson led a party up the Huxley. From a camp on Brodrick Pass ascents were made of Mc Kenzie and Strauchan in spells between the bad weather before the party dropped down the Landsborough via McKenzie Creek. Three days travel up the valley brought them to the Spence Junction and they then crossed to the Mueller via the screes under Spence and the narrow divide from just north of Spence over Scissors to Baron Saddle. Tom Clarkson, Neil Whitehead and Don Fraser went up the Rakaia in January 1967. They had five ‘almost continuously rainy’ days before crossing the Rakaia by the bridge near Meins Knob over Strachan Pass to a morraine camp just below the snout of the Lord Glacier. In murky weather next day they spent thirteen hours traversing four mi les of Lambert Gorge to the confluence with the Wanganui.

In 1968 two former members of the club, George Caddie and Arnie Allan, joined Keith Jones and Phil Burgess on a highly successful trip. Their route from Erewhon was up the Clyde to the Garden of Eden, down to the Perth, then into the Godley via Sealy Pass, over Pyramus to the Havelock and so back to Erewhon. In almost two weeks of fine weather they had time to climb Guardian Peak, Tyndall, Newton, and Farrar from the Garden and D 'Archiac from the Godley. Another largely fine weather trip was completed in 1969 by Bryan Sissons, Lesley Bagnall, Noel Sissons and John Keys. They crossed the Copland Pass to Douglas Rock Hut and from there after a rest day they pushed up Bluewater Creek to Scott Basin and Welcome Pass on the fifth day. A snow cave was put in and Sefton, Scott, Blizzard and Pioneer climbed before the party went down the Wicks to the Douglas Basin and Harper's Bivvy. A quick trip over Douglas Pass and a crossing from the Spence to the Mueller using the same route as Stephenson's 1962 party, but in a gathering nor'wester brought them to Three Johns for a short enforced sojourn before their departure down the Mueller.

This selection of Christmas trips made since 1950 hardly suggests the number of parties nor the variety of their objectives, but will, perhaps, give an idea of what today’s smaller groups can achieve.

See Appendix for list of major trips 1921-71.

Climbing

Christmas trips, by taking trampers to the more remote and higher mountains, have from the earliest times stimulated an interest in climbing. In the later twenties, parties frequently went to Tongariro National Park in the summer, when several ascents were made. The Kaikouras also attracted climbers, and in 1926 S.A. Wiren and others had got to the top of the main divide peak near Armstrong in the Waimakariri.

Generally, until after the war, there were few private climbing parties and most climbing was done by subsidiary groups from the base camps on Christmas trips. In the fifties and sixties, many more parties have set out specifically to climb; in fact they have been so numerous that one can only suggest the wider scope and often fine success of these efforts. And it is also in the nature of things that the more notable work has often been done on private trips and by members whose age has made their association with the club a little tenuous.

However, in the thirties the club did have its representatives in the exploratory kind of tramping and climbing associated with the name of J . D . Pascoe, when you often not only climbed your peak but named it too. S.A. Wiren with other N.Z.A.C. men in 1931 climbed for the first time Westland, Warrior, Amazon and Blair. Wiren, though no longer a student then, had been prominent in the club just a year or two before. Then, from the Clarke Glacier early in 1934, W.H. and R.J. Scott crossed Strachan Pass, skirted Mt. Lord and traversed the Lord Range to the Wilberg Glacier and made the first ascent of Dan Peak. Arriving on that isolated mountain at 4.30pm they spent a night out near Mt. Lord before returning to the Clarke. P.S. Powell, A.H. Scotney and J. Croxton were next in the field. In 1939 they pushed up the Perth Valley and from a camp above the bushline climbed the virgin Great Unknown, returning the next day for the view they had missed on the first. A similar kind of trip, depending on hard packing, was made in 1955 by D. Somerset, D. Millward, M. Rogers and T. Carter. After a few days climbing from French Ridge Bivvy they crossed over the Bonar and successfully prospected a route to the Waipara Valley floor, via a spur on the left of Fireman Creek. From there they found a new route on Eros, carrying full packs most of the way and weathering two days of nor'wester near the summit before going out over the Matukituki Saddle.

Over the same period the club was also active in the more accessible eastern valleys and mountains. In 1934 C.J. Read with his brother and guide Kurt Suter had a successful season in the Tasman, making the first traverse of Walter and collecting many other peaks including Green, Elie de Beaumont, the Minarets and Cook. The following year, W. H. Scott, Read, R. F. Kean, F. Newcombe and others were in the Godley. Various members of the large party recorded ascents of Moffat Malthus, McClure, Dennistoun and Wolseley, completed the first traverse of Victoire and pioneered the Trident route on D 'Archiac.

On the 1940 Christmas trip to the Waimakariri J. Witten-Hannah, J.B. Butchers and J. Gillies, climbing from the White confluence, made the first traverse of the Shaler Range, bivvying out one night on the ridge. But probably the 1945 Christmas in the Wilkin, when the club combi ned with an OSONZAC meet, was the best example of what could be done by climbers working from a trampers' base camp. R. Oliver, R. Jackson and F. Evison made the first ascent of Mt. Kuri, climbing from the Wonderland valley; others climbed Aeolus, Arne, Pollux, Lois and Turner, and A.J. McLeod completed the first climb of Ragan since the time when Charlie Douglas had reached the low peak in 1891.

In the 1950-51 season R. Ellis, S. Jenkins, R. Knox, J. Ardley and S. Martin were in the Franz Joseph. From a snow cave at Mackay rocks they climbed De la Beche and the Minarets before crossing Graham Saddle to the Tasman. A rather interesting trip organised by Ellis in 1955 had as its main objective Mt. Balloon in the Milford Track area. The climb, the third ascent, was completed by Ellis with G. Gerrard and E. Offner. Later on the same trip Offner and Ellis with Jacky Ellis climbed the west peak of Earnslaw by traversing the east. A couple of successful climbing trips have also been run in the Hopkins Valley. In 1955 D. Somerset and Offner climbed Hopkins, then from a camp near Elcho Col. Somerset and J. Thomson climbed Ward while Offner and E. Masters climbed Jackson and two days later each pair climbed the other peak. In 1960-61 a party climbed Ward, Dazzler Pinnacle and a peak, probably Armature on the Neumann Range.

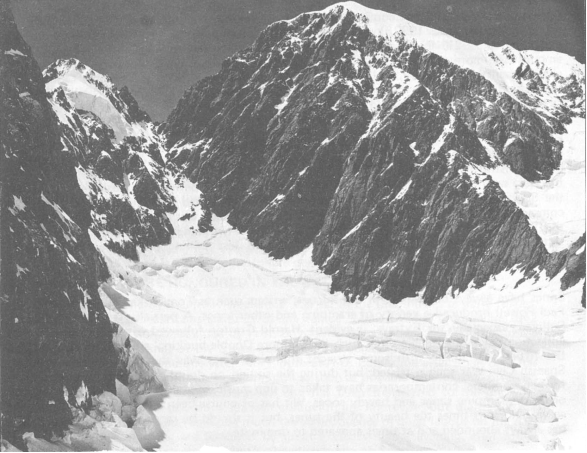

With the changing interests of later years, club members have gravitated increasingly to the two present centres of N.Z. climbing: Mt. Cook and the Darrans; although some people have also been attracted to other areas, notably the Rakaia, the Arrowsmiths and the Armoury Range. Parties have in general become smaller and more exclusively concerned with climbing as opposed to combined climbing and transalpine work. In the period 1960-62 I.D. Cave and J.G. Nicholls with M. Gill and P. Houghton of Otago University completed an outstanding series of new climbs in the Rakaia, the Tasman and in the Darrans. Ian Cave writes about these in a later section. In 1963 P. Barry with W. R. Stephenson put in a variation of the Marian route on Sabre. Four V.U.W.T.C. members - R. Gooder, P. Radcliffe, C. Bolt and N. Eggars had a successful 1968-69 season in the Tasman, all climbing Malte Brun and the west ridge of the Aiguilles Rouges. Gooder and Radcliffe climbed the south ridge of Green. The following year, Gooder, with J. Wild, made the second ascent of the south ridge of La Perouse and a Grand Traverse of Cook. In the excellent 1970-71 season at Mt. Cook, J. Keys, K. Jones and C. Timms climbed the Pioneer Ridge of Douglas and made the second ascent of the west ridge of Haidinger. Ross Gooder, climbing with a Canterbury climber, J. Stanton, made a direct ascent of the east face of Sefton and also completed climbs of the south face of Hicks and the Sheila face of Cook, with C. Fraser.

Obviously, these last few climbs were not made on club trips. But the club has become, as far as mountaineering is concerned, not an organisation which takes people climbing, but one which provides the facilities for individuals to meet and plan their own trips. And the success with which it carried out this function is amply proved by the outstanding work of recent years.

Mid-Year trips

Winter, despite the cold and the short daylight hours, has its attractions and draws more trampers and climbers into the mountains than ever before. In most areas, that much-prized sense of isolation can still be counted upon, whereas in summer the numbers in many valleys produce a kind of village life. And winter changes the mountains in many unexpected ways, rendering them strangely beautiful under their heavy snow.

In the early years, the skiers ran a continuous series of August trips to Arthur's Pass, Tongariro National Park and Egmont. These ended about 1947 when a separate Ski Club was formed, but the club mountaineers continued to go to Egmont and Ruapehu, not only in August but for weekends at any time throughout the winter. For in winter these mountains can give excellent practice in snow and sometimes in ice work; they have therefore been the scene of many alpine instruction courses. Some routes, such as the southern face of Te Heu Heu and the crater face of Tahurangi have in recent years given more experienced members a tussle.

Winter trips to the South Island have also increased recently. The Spensers have been an obvious choice, but climbers have also found that several of the more accessible Canterbury ranges, such as the Armoury Range and the Arrowsmiths, give excellent climbing in the often settled August weather. In fact trampers rather than climbers find the difficulties greatly increased in winter. A climber may still choose clear rock, but a tramper is almost certain to be faced with upper basins choked with snow. In August 1970 a club party completed a Three Pass Trip, but they had steep snow instead of scree and had to break through a cornice to get on to Browning Pass.

Easter was always the other main opportunity for a longer trip. Kapiti was once a favourite spot, and longer trips were made in the Tararuas. But in more affluent times, and with more private transport, pre-varsity trips, May holidays, Study Week and post-finals trips have made their almost regular appearances. The club has visited the Ruahines often, and much has been seen of the Kawekas and Kaimanawas also, access to the latter being improved by roads for the Tongariro Power Scheme. There are very few records of trips further north (apart from the Urewera), although in 1970 an ascent of Mt. Hikurangi was made at Easter, and the area has since raised some interest. But its isolation - nearly 400 miles from Wellington - is likely to preserve its peace, despite its reputation for primeval forest, very hard going and reputedly virgin peaks.

The days of the regular Christmas, Easter and August trips have gone. People go into the hills when it suits best and when the weather seems right. And this is sensible. The mountains may always be there, but a student's life is brief; and he has learned to make the most of it.

Outward and Visible Signs

General

B. A. Sissons

MANPOWER

The size of the club has always been difficult to assess, but it would never have exceeded a hundred active members at any given time. A list of 169 names was compiled in 1966, but this included many immediate past members and peripheral trampers. Active membership grew throughout the twenties and thirties to about 60 or 70 by the end of the second decade and with the return of many after the war, soon reached a peak of around 80. In 1947 the skiers, who in the preceding twelve or so years had become an increasingly active and identifiable group, left to form their own club. In the following years membership dropped, to stabilise at about 40, where it has remained since.

TALK

Activities have never been confined merely to tramping or climbing and the first club report in Spike, June 1922, gave notice of this: "Commencing operations only at the beginning of 1921, the Tramping Club has already become an institution recognized amongst the more venerable of college clubs. Freer than the Free Discussion Club, more gleeful than the Glee Club, and - shall we say it - Draughtier than the Draughts Club, it has found a place in college life." Discussion was fostered by shorter trips and large parties, and topics ranged from the finer points of equipment to more august questions of politics and literature.

Politics have been one of the main interests of club members and in a university tinged with more than a hint of red, the tramping club has been one of the more leftward leaning institutions. Rumours persist of jobs lost or jeopardised for political beliefs. After the war, with the return of an older, more experienced and perhaps disillusioned group, the Socialism and Marxism of the twenties and thirties turned here and there to active communism. For a time in the early fifties the Socialist Club was almost encompassed by the Tramping Club. But in the later fifties, politics were no longer a live issue, and in the sixties with smaller parties and proclivity toward less talking and more tramping, discussion in general became less important.

SONG

Songs have always been sung. In the thirties, writers such as Tom Birks, Ron Meek and Paul Powell produced a variety of tramping and other songs. A partiality to Gilbert and Sullivan, especially for Extravs, is evident. Harold Gretton followed with a magnificent collection, and some of his songs such as 'No more Double-bunking' are still in vogue. In the fifties folk music with some straight tramping songs was the thing, though one Spanish Civil War song persisted; but during the sixties, no doubt to the horror of some former members, contemporaries have taken to pop music, mixed with folk, and, as ever, ordinary tramping songs and bawdy songs. Wit has of course been a standard for judging songs, and sometimes the beauty of the tunes, but it should be recorded that bawdiness has always abounded and at times appeared to dominate.

TOWN HAUNTS

With a lack of a permanent headquarters, a discontinuous year's activities, and a short span of membership (averaging about four years per person) there is a problem of continuity in the club. In response to this, informal headquarters have tended to develop on occasions. In the fifties the Somerset house in Kelburn Parade was the centre for activities for about eight years. Recently, after a few years in the wilderness, the club has settled once again, this time in a flat at 143 Dixon St. These unofficial headquarters are a mixed blessing. They are more hospitable than the stark Students' Union and there will usually be someone round to talk to but they encourage a cliquishness which has at times detracted from the club as a club. Informal lunch meetings, which began a few years ago, but have become irregular since, almost invariably took place on fine, warm days in the graveyard beside the Students' Union, and did at least help to give the club an identity.

THE WRITTEN WORD

Trampers have always had a tendency to record impressions of their trips, thoughts about the hills, and so on. Records of the club appear from the Spike of June 1922 onwards. The coverage, especially in the thirties, was quite comprehensive including trip accounts and summaries of the year's activities. Smad followed by Salient contained a few articles - one of note in Salient told the story of the misadventures of Robin Oliver and Jim Witten-Hannah when they camped in the crater of Ruapehu during the 1945 eruption. In 1947 the first of what has been a continuous series of publications appeared. Containing news and trip accounts, this newsletter was published three times a year until it became, in 1952, the annual Heels. Cyclostyled and often difficult to read it does however contain a wealth of information. In 1968 a new-look Heels printed offset and including photos, was instituted by the editor of that year, Pete Radcliffe. This style of production has been maintained.

SKIING

From the mid-thirties to the late forties there was a continuous series of August trips to either Ruapehu, Egmont or Arthur's Pass. These were predominantly skiing trips. During that time a strong skiing section developed in the club, until in 1946 a separate ski captain was appointed. In 1947 a separate ski club was formed. Skiing in the thirties and forties was not quite the big business than it is today. At Ruapehu, 'varsity parties used to stay in now-demolished huts behind the Chateau. Tales of illicit use of the Chateau's facilities, with entry via the coal bunkers, and evenings spent dancing amongst Chateau guests, have been related with glee. And the skiing was good too. There was more snow, and people used to walk up from the Chateau, and often could spend the day skiing in places where today lack of snow would make it impossible. At the end of the day, one could even occasionally ski down the Bruce most of the way to the Chateau.

Skiing at Kime and on Holdsworth in the thirties was also common and inter-club championships were held in the Tararuas. Such activity would probably not be possible with today's small snowfall.

At all events, the skiers left. And, whether it is a coincidence or not, the character of the club changed in the following few years. In the early fifties the trend to smaller parties and in general probably a less social atmosphere pervaded except perhaps at bashes.

MORE HONOURED IN THE BREACH? NEVER!

Bashes, or more explicitly alcoholic weekends, started in the late thirties or early forties. The club photo album contains pictures of the famed 'Mulled Wine' reunion in 1942 when festivities were no doubt aided by Prof. Boyd-Wilson's acknowledged abilities in the field of wines and brewing. In the fifties bashes were brought to regularity - two a year, one at Queen's Birthday, and one after finals, both at A - D. Lately the after finals bash has disappeared, too many people leaving Wellington as soon as possible after exams, often on post-finals trips; and the Queen's Birthday one has been transferred to the mid-year break. Memories of these occasions, though colourful, are imprecise, but the pattern as far as can be ascertained has remained much the same. Scenes of great labour on the A - D track on Saturday morning are followed by great excesses in the evening, after which people may retire to the flats to sleep before heading home on Sunday.

Fashion

Tawhai

Tricia Healy

In 1932 a Lower Hutt builder received a wage increase - an extra 2 pound ten shillings to be added to his weekly 12/6 wage which he was receiving from the government. This generous wage was paid to him by Geoff Wilson, Mary (his wife), W. E. Davidson and A.J. Hilkie for his undertaking to build them a hut in the Orongorongos.

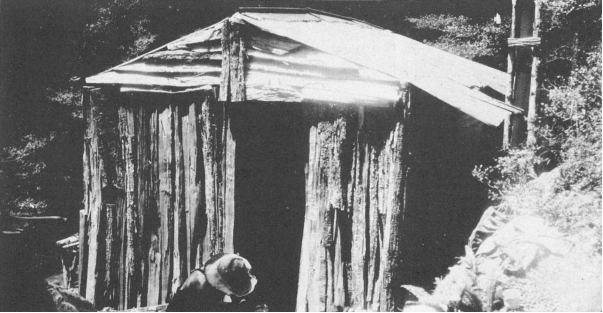

Unfortunately, no doubt, for him financially, the hut took only two weeks to build. Built of red beech slabs, the hut had a tin roof, a clay floor, was 11ft. x 12ft. and accommodated eleven (in five sacking bunks).

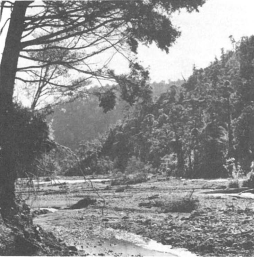

Tawhai, as the hut was called - named for its position amongst the beech trees and after Geoff Wilson's pen name - was situated on a terrace 80ft. above and on the true right of the Orongorongo River, just downstream from the end of the Five Mile track.

Built as a winter retreat (the Tararuas often being out at that time because of bad conditions), Tawhai had to meet certain requisites imposed by its owners. It had to be reasonably close to Eastbourne - one always walked to Tawhai from Eastbourne (although the Wainui Road was there, student-owned vehicles were unheard of in the 30's). It also had to be on the Eastbourne side of the river, where it would be free from the threat of winter floods, mosquito-free and a trap for whatever winter sun was shining.

The site the owners chose fulfilled all the above conditions, this being more important to them than the fact that it was disadvantageously situated 80ft. above any water. This last factor was largely overcome by a big kerosene tin hidden nearby, which, when filled once, supplied the hut for an evening. For those unfortunates ignorant of the tin's existence, or, if aware, ignorant of its whereabouts, it was a case of much energy and much breathwasting cursing being expended on grinding up and down to the river to collect a billyful at a time.

The usual method of getting to Tawhai was by catching a ferry to Eastbourne and walking to the hut from there. Of course if you lived at Eastbourne, as did many early club members, you just started walking. Either way you tramped over the Gollans Valley farmland into Wainui-o-mata, then over into the Catchpole and up the Five Mile track. From near the end of this you carried on down a small stream about 5 minutes before Jacob's Ladder. This stream has a steep bank on its southern side which you climbed 80ft. up to a terrace where was found Tawhai Hut.

In the 1930's, when Tawhai was built, a large number of students were part-timers, working Saturday mornings, which made full weekend trips an impossibility. Full-time students usually waited for their less fortunate friends, so most trips to Tawhai (and elsewhere) would have begun some time on Saturday afternoon. This perhaps explains the note found in an old copy of Heels: '...Tawhai where you can spend idyllic weekends swimming, eating, sunbathing and debating!'

Such occupations are supposedly foreign to today's tramper with much more tramping time available at the weekends and more recovery time available during the week, but to a student of the 30's these things would have seemed most sensible. Students had to combine university work with five and a half days employment and were given little time off for study and lectures. A tramper would have arrived at Tawhai late Saturday night or early Sunday morning, knowing if he went much further he'd be arriving home early Monday morning, feeling oh so like five and a half days' work. Many, in spite of this, did arrive home early on Monday morning, sometimes just in time for work, after having spent hours tramping over to the Wairarapa and back on the Sunday, or if they were less fit after hours of sliding round amongst the shingle and goats of the Mukamuka Valley.

1934 saw all the other Wellington clubs at work building their own huts - up till this time all hut-building had been carried out by the more affluent and longer established Tararua Tramping Club. Varsity, somewhat envious of all the other clubs with their new huts, and unable to build one itself on the grant of 3 pounds a year from the Students' Association, instead asked the owners of Tawhai Hut, who were all either ex-students of Victoria or associates of the club and its members, if they could buy a two-fifths share in their hut. This was finally agreed to and a formal agreement was drawn up whereby varsity could use the hut for twelve official trips a year. This agreement, the owners felt, was quite unnecessary for in actual fact the students were free to use it whenever they wished as had been the case before 1934. As a donation to the club Geoff Wilson paid the annual City Council fee of 1 pound and in return the club carried out maintenance work on the hut.

This somewhat haphazard situation and arrangement continued on through the thirties and war years, by the end of which both parties were beginning to lose interest in the hut. Geoff and Mary Wilson, the mainstay of the original owners, had moved to Auckland and consequently they were rather infrequent visitors to the hut, which was by now badly in need of repair. The other two original owners, W.D. Davidson and A.S. Hilkie were also infrequent visitors and 'varsity now had a new object of status to dream over and work upon: their own hut, Allaway-Dickson in the Tauherenikau. No longer interested in Tawhai unless they could own it completely, 'varsity wrote to Geoff and Mary in 1947, asking them if they would sell. The Wilsons were unwilling at that time, wanting to keep a share to pass on to their children, and with the building of Allaway-Dickson in 1948 and its subsequent completion in 1949, 'varsity, not unnaturally, somewhat neglected Tawhai.

In 1952 a student sub-committee investigated the possibility of repairing it. This was soon found to be impossible, its state being too decrepit, and they decided fund-raising for a completely new hut would have to be carried out. A new site, downstream and nearer water, was suggested, thus leaving the original owners with their 'hut' on its old site. Lack of funds prevented this occurring and by 1954, 'varsity, W.E. Davidson, and A.J. Hilkie had lost all interest in having a hut in the Orongorongos. This left the Wilsons, still in Auckland, in sole command of their by now derelect hut. In 1959 they wrote to the city engineer, asking him if he would transfer the site and licence to some reliable tramper. This was acceptable to him, but the new owner could not have been very enthusiastic for Tawhai was never rebuilt. Today, if one were to meet a person returning from Tawhai he would tell a tale similar to that of Shelley's traveller in his poem 'Ozymandias'. He would tell of the few old logs and bits or iron that still mark the spot, but would have to conclude, 'Nothing beside remains.'

Allaway-Dickson

K.B.Popplewell

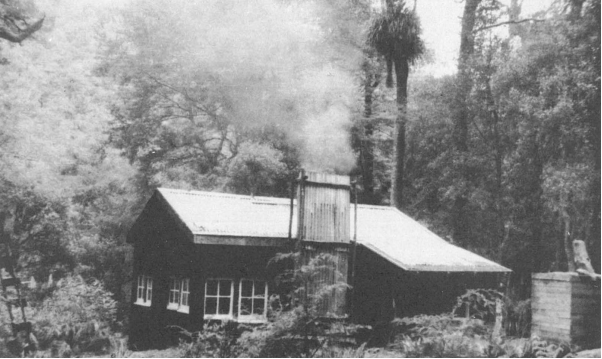

After the tragic death of Stanley Allaway and Roy Dickson in the Hopkins Valley early in 1947, thought was given to the provision of a suitable memorial. The initial plan, a plaque in the Elcho Hut, was soon dropped in favour of a hut in the Tararuas. This seemed particularly appropriate as for some time such a hut had been mooted. It was to be the club's first hut, apart from a share in Tawhai Hut in the Orongorongos.

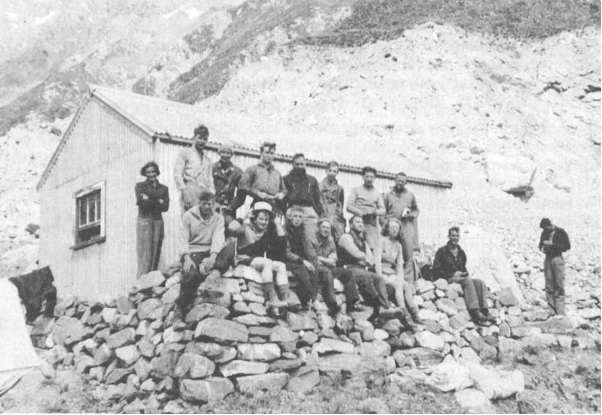

The best site for such a hut appeared to be somewhere in the Tauherenikau Valley between the Tararua Tramping Club's Tauherenikau Hut (the "Chateau") and Cone Hut, and preferably near the bottom of the Reeves and Block XVI tracks. Two main sites were considered, the present site and one a short distance upstream on the other side of the river. After discussion with other clubs, and despite some opposition, the present site was chosen, mainly because of its proximity to the bottom of Block XVI track, its freedom from danger of erosion, and the presence nearby of a stream which was thought never to dry up. The fact that the site was a reasonable Friday evening's tramp from Kaitoke and was directly above the main ford of the Tauherenikau also influenced the choice. A club member (unnamed) offered to lay a bitumen floor to overcome the problem of the boggy site, but nothing came of this somewhat improbable scheme.

In the first few weeks of 1948 the site was cleared and levelled, and drainage ditches were dug and filled with stones. By Easter construction had started, with timber for the main framework being cut out of the bush. By August the hut was a roof-less skeleton and sufficient timber had been carried in to sark the roof and board up part of one side. Finals were now drawing near, however, and no more work was done until the end of the year. Then, during the Christmas and New Year holidays, the roof was sarked, the Maori bunk started, and the first fire-place built. Unfortunately, the gravel for the concrete was insufficiently washed and the fire-place very soon collapsed and had to be rebuilt.

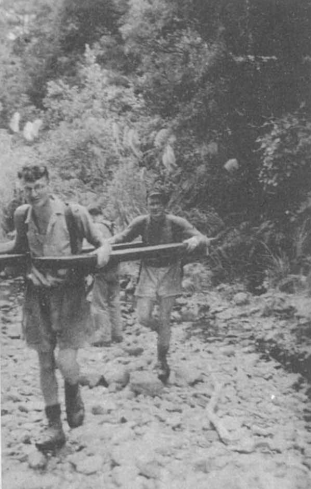

Back-packing of timber and other materials to the hut site had been going on for some time but a concerted effort to complete the carrying was launched on Anniversary weekend 1949. Harry Evison and Pip Piper devised an ingenious method of modifying packs to carry long lengths of timber. This consisted of pack-frames fitted with a three foot cross-piece of 2" by 1 ½" wood nailed or lashed to the bottom bar. Two people wearing these modified packs stood one behind the other about six feet apart, and three boards were placed on the projecting cross-pieces on each side of their bodies. It is reported that it then only required a man with a whip to set the whole machine in motion. Carrying was done in stages and dumps were positioned at both sides of the Puffer, at the Smith's Creek crossing, at Marchant Stream, and finally at the hut site itself. Everything went comparatively smoothly once the system was worked out, apart from minor mishaps such as a creosote tin springing a leak in Peter Jenkins' pack (sleeping the following night in his creosote soaked sleeping bag completely cured his influenza), and Peter Jenkins and Jack Liversage having to chase wind-borne sheets of corrugated aluminium half way to Masterton and half way up the Marchant Ridge respectively.

On 18 February 1949, in the pouring rain, the west side of the hut was covered in and provided shelter while meals were cooked in the half-completed fire-place (number two). Meanwhile, all the piles had been placed and Bill Lee and Jack Gibson were doing a fine job inserting floor joists with a faulty level. In late March, after several weeks delay due to bad weather, the roof finally went on, and by the end of March the hut consisted of two and a half sides, a roof and half a floor.

Finishing work (such as battens, windows and floor boards) continued steadily until, at about 4.00pm on 30 April 1949, the second fire-place was finally finished and the hut was formally opened by Bonk Scotney in the presence of about sixty-five people. The opening ceremony was followed by spirited celebrations, perpetuated as the annual 'Hut Birthday'. Though it has been a somewhat movable feast, it is nowadays generally held early in the second term.

A-D has survived twenty-two years of Tararua weather, but is no longer getting the care from trampers that an elderly and lightly-built hut deserves. True, several generations of 'varsity trampers have carried out maintenance over the years. The place was completely repiled in 1959-60, a new floor was laid in 1968 (gone is that beautiful rough-hewn floor in front of the fire), and the fire-place itself was rebuilt for the third time in 1970. But for all this it has become increasingly obvious that the hut is no longer standing up to the wear and tear of constant, heavy - and careless - use. To provide something better able to survive the onslaughts of modern trampers, the Forest Service plans to build a new hut a little further up river, when (though a reprieve is possible) they say the old hut will have to go. With it would go what for more than twenty years has been the club's largest undertaking and accomplishment; and the dream of those whose enthusiasm first got the building under way would once again exist only in the memory.

Cone Bridge

G.Caddie

In the May vacation of 1958 Bryce Evans and David Patterson perished in a blizzard on Mt. Hector. By June 1960 the bridge at Cone Hut had been built as a memorial to these two club members. Because, more than a decade ago in the enthusiasm of youth, I agreed to design the bridge, the present generation seemed to think I was well qualified to relate its history. From the rush that is upon me now because of a facile agreement to the editor's request I feel I must be still just as rashly enthusiastic now, as then.

Parental donations towards a memorial project started the ball rolling, and later the Students' Association made a contribution to the fund. A hut was ruled out by the club committee as Allaway-Dickson was considered a big enough commitment for the size of the club, and hind-sight tells that the importance of any such hut would have been diminished by the N.Z. Forest Service's hut-construction activities of the 1960's. How a bridge came to be decided upon I don't know but sometime in 1959 Ian Cave (then chief guide if I remember correctly) asked me to design the bridge, seeing that, amongst other reasons, I was the only civil engineer active in the club at the time.

My experience of trampers' bridges went from the sublime (two-wire jobs) to the ridiculous (Otaki Forks) with nothing in between. However, I spent a pleasant Sunday afternoon boning up on ideas by trotting up to Otaki Forks and giving that a good eye over. Next, armed with abney and tape I went with Ian and a couple of hangers-on to Cone Hut, after a hut bash at A-D.

Evidently the Forest Service had nominated Cone as the most suitable place for a bridge. Sites close to the hut were soon ruled out (although this is what had been in mind); the river was too wide and trees to support a bridge not available. Eventually the site upstream was chosen as the most feasible one available.

A few sums from the measurements taken there and it wasn't difficult to decide that the material for the bridge should be prefabricated and flown in. A few more enquiries showed the cost of doing this to be more or less within the bounds of the finance available and sighs of relief were heard all round. The timber was all delivered to Popplewell's at Naenae in the first term of 1960 and a variety of people cut it, bored it, painted it, marked it and bundled it up. Meanwhile Ray Hoare organized the steel hangers and such-like hardware.

My calculations had been based on seasoned timber, but it rained fairly often while the timber was being prepared at Pop's place and to boot, the timber merchants had supplied timber nearly as green as we were at bridge building. The result - at least one helicopter load of water was ferried from Kaitoke to Cone. Also I suppose if I were to design it now I would find ways to cut down on the size of some members. Perhaps that would have relieved the troublesome trees a bit - though not much.

The general idea had been to get the bridge built in the May holidays and a helicopter was to be available one Friday to ferry in all the materials. I took a day's leave and shot up to Cone with Steve Reid to be there when it all started to come in. No such luck. On Friday it blew a gale and we amused ourselves as usefully as we could. On Saturday hoards of people began to arrive and Ewan McCann announced, "The helicopter didn't arrive from the South Island because of the wind yesterday. It will come today." Oh yeah, I thought, as it was still blowing and also trying to rain. A vastly overcrowded Cone Hut didn't appeal much so three of us departed for Allaway-Dickson. Those who were left wished for a bridge next morning as the Tauherenikau had risen enough to deter all but the most determined.

Some time later in the May holidays Ray Hoare saw all the material stacked up near the site and a couple of week-ends in June were sufficient to get the bridge built, with various people claiming just as various first traverses of it. The decision to precut the timber was vindicated and all the hangers seemed to be the right length. There was some trouble on the right bank and adjustments were made to give easier access. I hadn't been able to come up either week-end and it was a couple of years before I saw a slide of the bridge, and realized it had been hung on different trees from the ones I had selected.

Over the years the right bank trees, one in particular, have sagged slowly but surely under the weight of the bridge. Measures to halt this sagging have occupied the club on numerous occasions since then. A concrete block was put in at one time as a foundation for a prop under the upstream tree but the prop was never put in, and it's hard to say how effective it would have been anyway. However, from time to time exaggerated reports were received that the bridge was in a state of imminent collapse and this led to an inspection in 1967. It was found to be quite usable and appeared likely to remain so if some maintenance work was carried out. This would have involved renewing hanger support bolts, painting some of the timbers and possibly completing the prop for the tree. But before any of this was done, that tree on the left bank collapsed and the bridge was in the river. It has since been attached to a new tree and hoisted into position again, where may it long continue.

Cone Bridge 1970: repair work took almost as long as original construction

Instruction Courses

T.S. Clarkson

As a university club is of necessity a group of young people, the need arises for instruction courses in skills associated with tramping and alpine activities.

In the realm of bushcraft the need is not very great, if judged by the lack of success of instruction weekends run by the club. University club members are at least seventeen years old when they begin tramping with the club and by that age they have frequently had some introduction to the bush, either privately or with some youth organisations. This minimum age is a feature not found within other clubs, which must, perhaps to protect themselves, run educational courses in bushcraft skills for their rather younger membership.

Most techniques in the bush are best learned by experience, by observing and taking advice from those who have survived inexperience; and certain others, for example, the more sophisticated art of navigation, by actually leading trips. River-crossing is perhaps the skill which most needs practical demonstration. Although courses were seriously considered within the club as early as 1950 it is only in the last two years (1969 and 1970) that formal courses have been organised and held in the Tauherenikau Valley. Nevertheless, it seems that these courses, in spite of able and competent instructors, can achieve but limited success because that which is most needed in the bush, experience, cannot be acquired in one weekend.

Of rather more value have been the alpine instruction courses (AIC). These have been formally organised within the club for about thirty years and it is perhaps remarkable that the form of the AIC is the same in 1970 as it was before 1950 - though for some reason it seems that to be a pupil on an AIC today does not give one quite the status that it did in the fifties. The AIC has been the responsibility of the Chief Guide who in almost every case has taken a leading part in the organisation and the instruction. A brief resume of AICs in the past ten years gives some idea of the type of course through which the club has now introduced hundreds to the snow techniques used in tramping and climbing. Ian Cave was Chief Guide in the early sixties and his courses, with about a dozen pupils each time, took the form of several single days' rockclimbing instruction, followed by either one or two weekends of basic snowcraft instruction on Egmont or Ruapehu.

Bill Stephenson's course in 1963 was similar although a week at Kapuni Lodge on Egmont was involved. Bill was the only instructor. At about this time Bill and Peter Barry, a climber, who even at this stage of his youth had made notable ascents in the Southern Alps, attended an FMC instructors' course, and the 1964 course, as direct result of this, was perhaps the best arranged of this era and should stand as a model for future courses. The basic programme was three lectures, one on rockclimbing and two on snow techniques, with two full days at Titahi Bay followed by a weekend at Ruapehu in July and a week on Egmont in August.

Peter and Bill spent time producing instructive slides for the evening lectures which went off very welI as a result. Only seven pupils completed the entire course but with extra instructors on the practical part of the course the pupil-instructor ratio was probably as favourable as it has ever been.

Peter Barry took a major part in instruction courses up tilI 1967 when his departure for the Andes and residence in Peru ended his activity with the club. The 1965 course was of the form of earlier courses but as an extra Peter arranged a week trip to the Waimakariri after finals for about eight of the pupils. Any hope of success for this idea was simply washed away by the heavy rain which poured down for the whole time the party was in the Crow Valley. This scheme has unfortunately not been tried since. In the years 1966-70 the AIC has reverted to the earlier form, only one weekend of formal instruction on Ruapehu or Egmont. Success has varied, weather and snow being the determining factors. In fact, this type of course is too vulnerable to the whims of the weather gods and on several occasions, for example 1968, the amount of useful practical instruction has been minimal. However, in the more recent years increasing affluence has allowed those interested to make many more trips to the North Island mountains where the experience is gained.

Perhaps the most realistic evaluation of the worth of the club instruction course is to consider the number of climbers produced, perhaps by noting how many still have an active interest in climbing five or ten years later. Too often it is found that many never advance their climbing beyond AIC pupil standard, perhaps being interested in snow techniques only as a part of tramping rather than as a prerequisite for active mountaineering. Nevertheless, from every course of the past ten years there is at least one active mountaineer today who would certainly do credit to the VUWTC leaders for an introduction to and encouragement in mountaineering.

Gorges

J. R. Keys

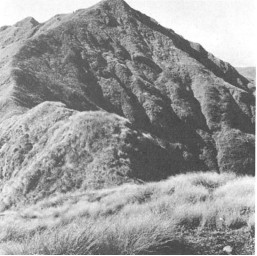

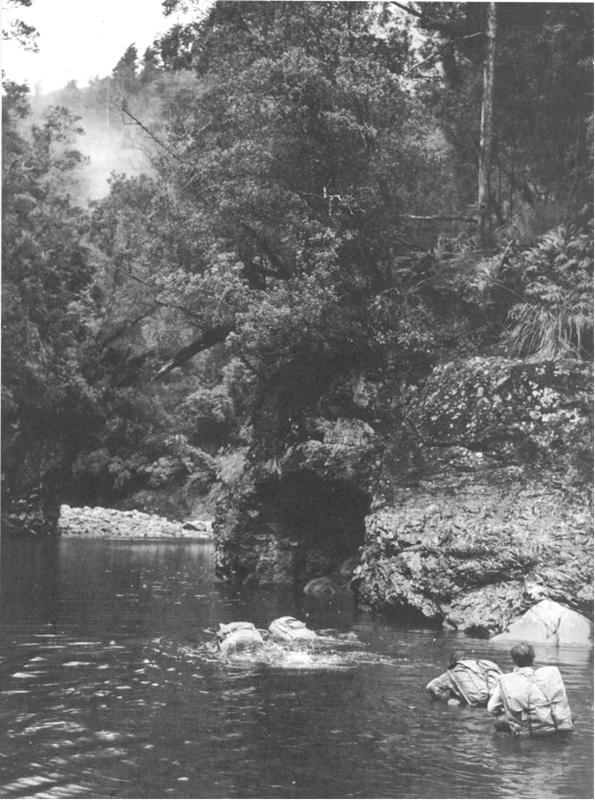

Geologically speaking the Tararua Range is an example of a growing anticline. As the land is thrust up, the rivers cut down and gorges are formed where the rivers flow through adjacent high country. This antecedent drainage pattern is typical of the Tararuas, especially along the Wairarapa side. Gorges have been liberally cut throughout the range and each of the rivers has at least one 'gorgeous' section.

The longest river in the Forest Park, the Waiohine, has miles of impressive gorge scenery, with its overhanging rock walls almost touching in one or two places above Hector Forks. Interesting folds and deformations of rock strata are revealed in several places, and long, though narrow, pools offer easy travel. The upper Ruamahanga is also rather impressive in places but there are few large pools and less swimming is required. The Otaki gorge is fast flowing and contains many rapids. Waitewaewae is 1100' above sea level while Otaki Forks are only 300' above sea level. Gorges such as the Ohau, Waingawa, Hector, Atiwhakatu, the lower Tauherenikau and Ruamahanga, and Hutt offer easy though interesting travel especially on a warm day. Several of these can be traversed for much of their distance on lilos, and have only small walls though these are waterworn and smooth. The volume of water flowing through these lesser gorges is not great on a fine day but in or after heavy rain the gorges are places to keep clear of. The lower Mangahao gorges are especially endangered in this respect by the dams, but they are still very good with many compulsory dips, big pools and rapids. Generally water flows gently in the lower gorges where the rivers leave the range, so that the swimming tramper must swim very hard to keep up, literally. However in the upper gorges a much faster rate of water fall is characteristic, for example the Ruamahanga and Waingawa.

All Tararua gorges are negotiable in fine weather but in 'average' Tararua weather they are usually impassable. It is not surprising that most through-travel is along the ridges though parties are occasionally forced down to the gorges in bad weather. It is then that 'sidle' becomes a dirty word. It would not be surprising if a future generation of Tararua trampers had one leg shorter than the other!

Most Tararua trampers have only brief encounters with gorges on the course of a trip, and it is only since the last war that the term 'gorge trip' has come into existence. However, the earliest recorded gorge trip was pre-war. It was led by Prof. Boyd-Wilson and featured the Whakatiki Gorge, Upper Hutt. Whenever the water was too deep for wading the party 27 sidled over bluffs and on one of these, a 'steepish, mossy slope ', a person slipped and slid down the slope, gathering speed and heading for a hundred foot drop. At the edge he was stopped by an ake-ake bush growing there, and was subsequently rescued by means of long birch saplings.

By 1951 river trips were becoming popular and the July Heels of that year contained an advertisement for the subsidiary Swampers Club. Membership qualifications for this club were two river trips. Some gorges were treated with disdain - particularly the lower Waingawa in 1951 during a working party attended by club members. One person was reported 'swimming valiantly with his nose upstream but moving steadily towards the sea'. He had a load on and the river was a Iittle high.

The first record of lilos being used refers to a trip down the lower Tauherenikau gorge in March 1952. There was at least one puncture, probably by one of the group with 'an otter complex'. It must be remembered that the phrase 'sink or swim' does not offer any reliable alternative when applied to gorge negotiation. Heavy boots, bulky pack, cold weather and cold water mean that even if you can swim, travel tends to the unpleasant. The earliest method used for pool negotiation was 'pack floating' and this is still common. The tramper wades into the pool until it becomes too deep. At this stage he must start swimming using a hybrid style - a cross between the dogpaddle and the breaststroke. This style is hampered by the pack and shoulder straps but has the advantage that if your pack stays on your back, your gear (usually) stays dry. A more sophisticated method is to throw your pack into the pool, leap on top of it and lazily paddle with your arms. The length of pool that can be traversed by this method depends inversely on the porosity of your pack, but it has the advantage that you often stay dry. Since 1952, though, lilos and inner tubes have replaced this latter method as a means of positive flotation. By clutching the tube or lilo to your chest, both you and your gear have the opportunity of staying dry though in practice you still encounter the basic problem of gorge trips - that of keeping warm. A worthwhile method of gorge negotiation for the fair sex is to become a parasite, sticking to some manly, broad back in the deep places. This was done on the lower Tauherenikau gorge trip of '52. Nowadays even more modern aids available include polystyrene rafts and collapsible canoes. Unaesthetic? Enough of masochism, we're out for enjoyment. Anyway suitable dead trees are hard to come by and have far too deep a draught.

With this in mind we come to recent gorge trips, skipping over the descent of the upper Tauherenikau gorge in 1954 where there was 'hardly a stretch where the roar of falling waters was unheard', and also over the 1961 Gollans stream trip and its temporarily missing party members. In 1968 a 'varsity party negotiated the Otaki gorge and only managed to lose a few spectacles and all warmth and dryness. Some people were rescued from the brinks of waterfalls, others were not and washed up on convenient boulders. A pack 'lodged under white foaming water was more difficult to rescue. The full Waiohine river was traversed in 1969, and the full Ruamahanga in 1970 by 'varsity trampers. They say in the books concerning safe tramping to take lots of wool. Well then, for gorge trips take lots more (a whole flock of sheep?). Things like wet suits, thick grease and hot baths are also necessary.

Throughout the years some gorge trippers have not discovered how heinous it is to sidle. In 1952 one person 'emulated the chamois' on the bluffs above the lower Tauherenikau river, and in '54 a falling rock hit an unfortunate lass while the party was sidling on deer trails, above the upper Tauherenikau gorges. In 1969 a sidler of the Waiohine gorge became covered from head to foot in bastard grass seeds. Still, the practice of avoiding horrible water on gorge trips undoubtedly promotes rock climbing. Shivers up to a foot long have been recorded in the Waiohine river - you must admit there is some incentive to sidle. All in all, 'varsity trampers should have become pretty much at home in gorges, and have grown experienced at river crossings and lifesaving. A taste of Tararua gorges certainly leaves you less in the lurch in the more famous gorges of the West Coast. And remember there are no routefinding problems in gorges - just head downstream.

Pack floating in the Mangahao Gorge. February 1965

Five Decades

A Few Misty Memories

J. Tattersall

It all happened so long ago.

And I plunge my hand down into the lucky dip of memory and what does it bring out? Scraps of sights and speech and people. Some clear, some clouded and misty. The smell of smoke in the bush and dripping trees, the whistling of cold wind and sunshine and glare from boulders and from snow.

Yet some early images persist - the inaugural meeting in a side room of the old V.U.C. Gym - a handful of would-be trampers - Bobby Martin-Smith representing the Students Association, there to assist at the Nativity and to give official cognizance and recognition - John Myers elected chairman, pleasant, informal and slightly inaudible. Another image of events some few weeks later. The new Club's first big trip - in the morning sunshine on the Rona Bay Wharf. An enquiry from me, well intentioned but slightly patronising, offering to help a new tramper with a hopelessly insecure, bulgy bag, secured with a strap, by way of a swag. His ready assent and then when I knelt on it the sickening sound of a china plate inside it breaking.

Of boiling fish in a steady downpour of rain but in the shelter of forest trees in the Orongorongo - fish caught that morning in Palliser Bay and lugged over the Matthews Saddle in a thunderstorm.

And strong recollections of our guide and guardian, E. J. Boyd-Wilson - "the Prof." Perhaps the strongest that of his swag consisting of sugar bag and cord. He was the only man in my considerable experience who carried such an object with apparent comfort and without cut shoulders.

And a fairly clear image remains of a three day tramp into the Waiorongomai and back over the range to Upper Hutt - or thereabouts. Our most distinguished guest, brought by the Prof., was G .S. Peren, newly arrived from abroad and destined shortly to command at Massey - on this occasion immaculate in corduroy breeches, stockings and with walking stick - his pack I do not recall. And notwithstanding arduous walking and rain and a crawl on hands and knees under some hundreds of yards of mountain scrub with irreparable damage to the corduroy breeches and - I fancy - a lost walking stick, his spirit and endurance impressed us and belied our too critical assessment of his undue elegance.

I remember too our trip on the then rather ill-defined route through the Urewera down the half-flooded Whakatane River and our over-intimate acquaintance with the brown waters of it, and the ultimate arrival at Ruatoki with food supplies exhausted and our entry into the store through the back door - it being Sunday - to replenish ourselves. It was on this journey that we formulated the interesting climatic conclusion that rain fell every night in that region. My own special tribulation centred on the party's large blackened porridge billy, of which I was the carrier - on top of my swag - and which seemed invariably the last article available for packing.

Most of all I remember companions many dead but few forgotten - our arguments and discussions and their surprising cheerfulness and endurance. I think of our man Phil who insisted on going armed with a rifle down the then little known Marchant Ridge of the Tararuas, against possible attacks by reported ferocious wild cattle, and the apprehension of the man following immediately in Phil's wake, who on steep descents often found himself looking down the barrel of the rifle which he had been assured was loaded. But it all happened so long ago.

The Thirties

A.G.Bagnall

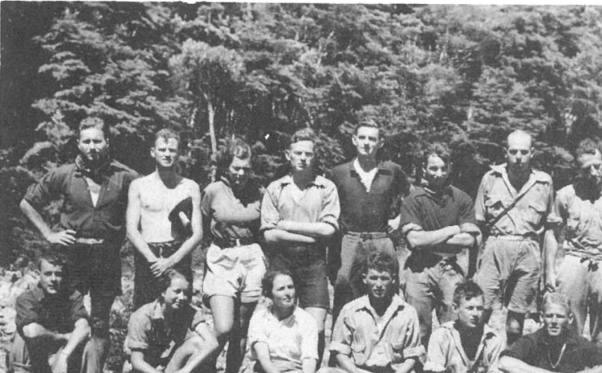

The haste with which one grasped this assignment gave way to a lengthy period of anxious cogitation, doubt, uncertainty, even scepticism about one's ability to define the precise character of tramping in the pre-war years - with a belated awareness that whatever one writes will be a restricted personal impression open to correction or challenge from any surviving contemporary. First of all, perhaps, one should try to answer some questions: who tramped, and where? - deferring to another place the possibly more interesting problem of why they did so. In retrospect the tramping circle looks something like a spiral nebula. At the centre the dedicated trampoholics, compulsive week-enders whenever possible, examinations not dissuading; in the next layer a less passionately devoted group who would turn out for a few trips a year, some clubtrips, some private. On the outer arms of the nebula the more numerous samplers who would grace a Christmas or an Easter expedition with their presence and patronise one or two Sunday or week-end excursions; and this for a wide range of motive: an attractive area, something new, a prestige journey, because "X" was going, or, more simply, the occasional urge of the hills. Others were of divided allegiance, played hockey, football or ran with the harriers; then even more than now it was something to be on top of Kaukau or Belmost Trig in mid-afternoon and on a snow-covered Hector at midnight.

The Club: the membership as a whole through the decade might be grouped into three generations. The first, when the writer joined in 1931, seemed, in the eyes of an impatient teen-ager, a fin de siecle group of survivors from the twenties, remotely elderly, female-dominated, nominally headed by a much-talked-of-father-figure, E. J. Boyd-Wilson. Quietly pushing through this restrictive undergrowth was an already maturing group of students some of whom were to be the leaders of Wellington tramping in the mid-thirties. From 1936 the core of the nebula changed again to be formed mainly of the vigorous masculine irreverence of the immediate post-war generation.

But who? Boys and girls, men and women, chiefly scientists and lawyers. The writer's memory is again possibly at fault in claiming the dubious distinction of being virtually the only regular male arts faculty student, although later there was someone called Scotney and for a short time J. D. Freeman. Some of the dedicated women were of this faculty as were many of the uncertain supporters, but a 1932 Mount Orongorongo trip is not untypical: one chemist, one botanist, two engineers and a meteorologist plus A. G. B. and this before the days of Gabites, Watson-Munro and J. B. Taylor. In an era of few full-time students the club seemed to suffer particularly from the annual loss of many keen members to the South Island professional schools.

Before one continues with further name-dropping, it is the writer's feeling, challenged by at least one indignant contemporary, that as the decade advanced club boundaries wilted or were disregarded by joint trips from a membership which was Tararua as well as Varsity. When the writer joined the Tararua Club in 1929 it, too, was an older generation organisation to be transformed in the mid thirties by an over-spill from Varsity and the more durable 'scum'. In the thirties for many of us club boundaries for a time ceased to matter except for the basic office-holders, committees and trip leaders. But here the point holds. G . B. Wilson who himself had long scorned the T.T.C., in a generous tramping young "middle-age" led key University trips such as Tararua crossings as did Tom Smith and others. F. B. Thompson tried out his passion for organisation on a reluctant student body and then happily graduated to the secretaryship of the T.T.C. And the truly famous women of the period, Huggins, Shallcrass, Singleton with their partners from southern universities, Mary Ewart and Betty Lorimer, made nonsense of club boundaries. In retrospect was this or that trip Varsity, T.T.C., or private? It was and is irrelevant, but what is important is that for the years of their direct and indirect association these women with others gave tramping a standard and character which was basically that of the V.U.C.T.C. Their independence, their willingness to route find for themselves not merely in the Wellington hills but in the Alps set a pattern for those who followed.

The kind of trips: the freshers week-end that few if any freshers ever had the temerity to venture upon, intellectual trips in the Orongorongos - the alcoholic ones only crept in during the last years of the decade - brain twisting camp-fire discussions when to the annoyance of the physically dedicated, people like Max Riske would go on - and on; Christmas trips for those who could afford them; the highlights, the Wairau and the Kaimanawas, building up from the Waimakariri to the Rakaia and the Godley. Prolonged journeys through the North Island hills and the Southern Alps, even making some first ascents of bumps that Pascoe and the C.M.C. hadn't quite got round to. And of course the searches, not highly organised L. D. Bridge S. and R. operations but wide sweeps through the Tararuas for days, even weeks, at a time. One's first tramping memory is as a school-boy seeing Bobby Martin-Smith in 1927 wearily climbing the hill to Firth House after the Diederich-Scanlon operation.

Where they tramped has already been answered in part. The Great Depression hit New Zealand in 1930. Even those in established positions didn't lightly dash off across the straits for a three-day weekend. It was not until 1934 that any but the most assured or financially courageous ventured far afield except at Christmas. Why didn't we hitch more? So it was the Orongorongos and Tararuas. In their pre-landrover maturity the 'Orongos' were still a magical area to which even the trip over was fraught with hazard, the track dangerous with challenge - from the 'dark hoozler' who could leave one struggling at the last bog before the saddle as he disappeared into the Turere, or, greater humiliation, to be left behind by the graceful feminine figure of the 'Red Terror' whose light-footed speed embarrassed many a husky male. But even the Orongos cost money as the old trip-book shows: a mid-winter ascent of Papatahi seems to have been really extravagant. "Fares 1/6" - good old Cobar - "Bread 6d. Rice 8d. Butter 7½d. Honey 10d. Chops 1 /-" a total of 5/1 d. but of course the honey would have done for another two weeks if it didn't tip upside down in one's pack.